Monday, February 1, 2021

Photography: The Art And Science Of Racial Oppression

Part I: Shaping the Narrative of Culture and Race

(Submitted by Chelsea Jones). Since the invention of the camera, the images we created and the photographic industry has been fraught with issues of inequality, inequity, and oppression that continue to this day. As with the industrial revolution and the current age of technology, with innovations come distinct benefits as well as consequences. Created and developed in the Victorian era by French and English inventors, the camera and the images it produced was as the intersection of art and science. 1 This development of photography took place when positivism was the dominant scientific ontology. 2 This led to a strong faith in machines, known as ‘machine objectivity’, since they were regarded as more objective than individual human perception. 2At that time there was little question that a photograph was an accurate and truthful representation of the subject.1 Photography, like any form of representation, was and is a social practice whose connotations were organized through cultural ideas and contracts, and is inherently problematic with roots in colonialism, government oppression, and racism especially towards the black community. 1

Without knowledge of this history, and current diversity and inclusivity issues surrounding race and culture within the photography industry, it is impossible to improve and grow as a photographic organization as well as empower talented creatives to engage in the art as a profession or leisure pursuit. We cannot, as an organization and industry, know where we are and need to go without knowing where we have been. In honour of Black History Month, let’s take a look at the role photography has played in the current racial climate and discourse of the 21st century.

The Story of the “Others”: Shaping the Narrative of Culture and Ethnicity

Documentary photography has routinely been a colonial art form, predicated on the notion that Europeans are better and sharing the narratives of “the others.” 1In decades prior, anthropology and ethnography have been utilized under the guise of science and research to further dehumanize those native to colonized lands through photography and a Eurocentric narrative. Colonial anthropology was not a study of culture but a study of difference in comparison to the ‘superior’ European race. 1 The use of photography to represent European superiority in Sub-Saharan Africa was one of the British and French Empires’ most powerful weapons of propaganda. Paired with the “factual” nature of the photograph, governments were able to manipulate the narrative of the population whom they believed to be uncivilized and/or “primitive.” 1 They displayed images of Europeans in positions of dominance or comparatively “civilized” poses, reinforced by lighting, styling, and propping. 1 Using light and dark colours was also utilized to manipulate a narrative by European Christian missionaries. Christian missionaries were often posed in light coloured clothing which would contrast with the dark clothing and skin tones of African people. These produced connotations of light/dark and good/evil juxtapositions that someone from European society would immediately recognize from Christian and previously pagan influences. This fed into the discourse of the civilizing mission often used as a justification for colonial rule. Photographs taken in an anthropological context portray ideas of race and hierarchy and pass them off as scientific fact. 1 Under the banner of anthropology, the differences between Africans and Europeans, often including measurements, documents of daily activities, diet, and religious practices, were exploited in order to contrast against the cultures of Europeans. 1 Back on European soil, anthropologists would publish papers about how colonial Europe was “helping” these people whose cultural differences were considered primitive and uncivilized.

Religious convictions, racial discourse, and photographs depicting these social interactions created a systemic disempowerment of people of colour. 1 This still can be seen today with the circulation of photographic images that portray Sub-Saharan Africa as an underdeveloped land ridden with disease and death and are often awarded in photography and journalism competitions. The images may evoke emotions; however, we are now more equipped to discern that due to the subjective nature of photography, the narrative is likely that of the photographer rather than the subject. That is, the bias and storytelling of the photographer is what is shaping our worldviews. It is important to acknowledge that our ongoing biases of developing nations have come about unconsciously, but still feed into the current discourse and perpetuation of stereotypes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: 2020 Google Search Results for, "African People."

Figure 1: Search results for “African People” on Google still perpetuate stereotypes that are rooted in colonialism (creative commons license).

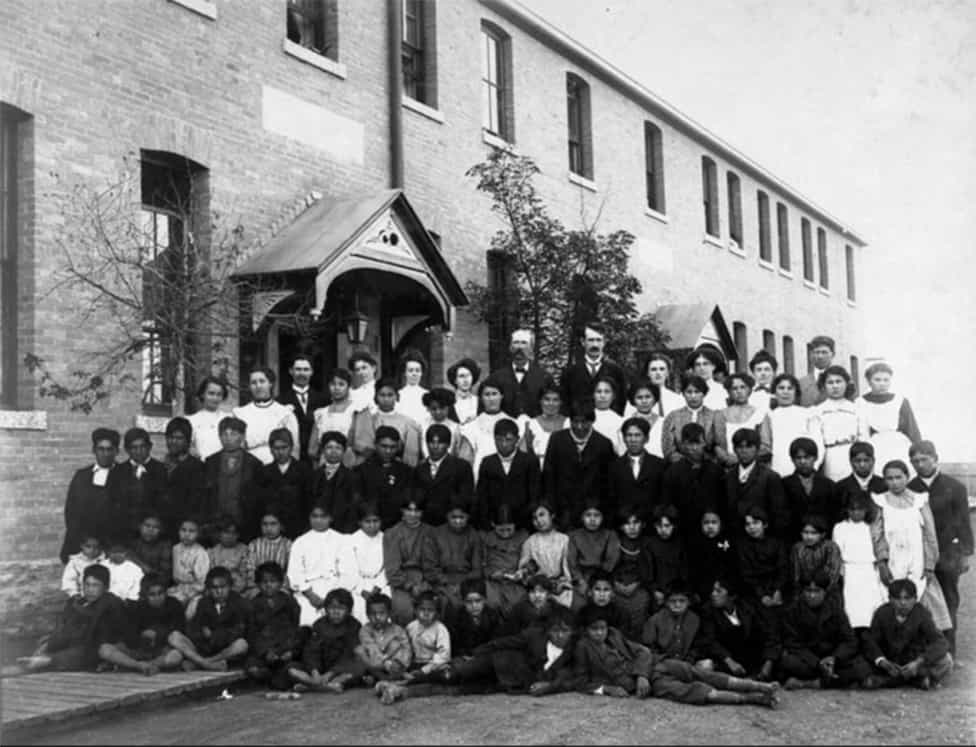

Canada has not been immune to these issues. Interestingly, there are many similarities, including the deliberate light and dark staging, in the European images of interactions with the Indigenous Canadian population involving fur trade or those of residential schools (Figure 2). Residential school images within history books and museums often show the Christian priests and nuns in regalia next to children dressed in plain clothing lined up as in school class images today. The photographer was typically a white male employee of the government who was executing a job that he was being paid to do, to create a certain narrative. It is, in part, due to these images that we, as a Canadian society, are only in recent years becoming aware of the atrocities which took place within the residential school system. The narrative of these images is that of the church and state at the helm while the children comply with what they are told; unable to tell their story.

Figure 2: Children and Faculty of a Residential School in Regina, Saskatchewan, 1908.

Figure 2: Residential school group photograph, Regina, Saskatchewan, 1908

Image online from Library and Archives Canada in Public Domain. 4

Underrepresentation of Black Photographers

Canadian artists from minoritized groups remain underrepresented in the historical and contemporary art collections and museums all over the country. One example of a Black photographer who has yet to be recognized in Canadian art history, is William "Billy" Beal. 3 Beal was an avid photographer and spent years documenting the people, events, and activities of his prairie community in the western Manitoba region. 3 Common images of Black people that circulated in Canada were primarily racist and dehumanizing, and commonly included blackface minstrelsy and people in positions of servitude. 3 These are images that many Canadians feel are “American,” and not representative of past Canadian racism. Despite this, Beal challenged this norm, as well as the racist Canadian laws of the time, and produced images of prairie life controlling the narrative and telling stories through his non-white lens. At this time in Canadian history, his very existence as a black person put his health and safety at risk as black people were not permitted to own land or immigrate across the 49th parallel as per Canadian law. 3 Billy Beal is just one of countless examples of black Canadian artists who has yet to be recognized as a historic photographer in Canada.

Barriers to Engagement in Photography as a Profession

As professional photographers, artists from minoritized groups experienced increased barriers to opportunities, such as resources, mentorship by like peers, and representation, limiting their access to the training required for professional designation, such as that as a professional photographer. 3 This likely stems from the Victorian era when slavery was only relatively recently abolished and racism was directed towards the black and the immigrant population of whom white society put deliberate barriers in place to limit their success in the workforce. These factors dictated that the ladder for these minority groups to climb to attain a profession was much higher than that of the white society. Resources were/are a considerable barrier as photography requires large initial purchases of equipment, space, leisure time to learn the craft and/or formal training, and consumables such as film. Although situations in society have improved for these minoritized groups, the socioeconomic impacts last to present day meaning equality to access and resources has not been attained and equity is part of the equation in approaching present day diversity and inclusion issues in the photographic industry. Over history, it has been largely by design that barriers remain in place for minoritized groups so they are unable to enter professions and trades, or even join leisure groups such as photography clubs.

It is important to acknowledge that as Canadians, we have, as a society, an oppressive and racist past, including anti-blackness. We must gain knowledge of to move towards a diverse, kind, compassionate, and inclusive Canadian society. With education, diversity and inclusion initiatives, empathy, and kindness, we can collectively work to grow into a community where professional photographers can thrive despite and because of their intersectional factors which bring unique perspectives, creativity, and engagement throughout our community.

References

- Mabry, H. (2014). Photography, Colonialism, and Racism. International Affairs Review.

- Wevers, R. (2016). Kodak Shirley is the Norm: On Racism and Photography. Junctions, 1(1): pp. 63-72.

- Fearon, A. (2020, August 20). Why you need to know about Billy Beal, the great unsung Black photographer of early 1900s Manitoba. CBC Arts.

- Woodruff, J. (1908). Indian School [online]. Library and Archives CanadaPA-020921.

Article by Chelsea Jones.

About the Author: I am a professional photographer, occupational therapist, and Ph.D. Candidate. I am also keenly aware that I am a cisgender, white, privileged Canadian woman writing about topics related to race, intersectionality, diversity, and inclusion. I write this as part of my own journey of trying to become more knowledgeable and educated as to be a better human to others in the photography community and society. It is a strongly held believe of mine that history is the key to understanding our past, present, and improving our futures. I am not trying to represent or speak for any persons or groups of people. Despite my best efforts, I will not get everything in these articles right, as I have my own biases (those that I am aware of and those that I am not) that shape my worldview. Every attempt to reference sources and limit my own opinions were utilized; however, it was noted that there are very few publications on the topic of diversity, race, gender, intersectionality, and inclusion pertaining to the photography industry. I hope that by sharing some of the things I have learned through my journey will spark interest in others in the photography industry to dig deeper into their own biases, views, history, and current discourse within the industry and society.

Chelsea is a Master Photographer (MPA) with the PPOC, earning 20 Accreditations. She holds National Board Postions as the Accreditation Chair and a Member of the Diversity And Inclusion Committee. She is a recipient of multiple Regional and National Best In Class Photography Awards. She is located in Edmonton, AB and her business website is: Vitality Images Photography.